In the quiet hum of a studio, a new kind of chisel is at work. It isn’t held by a sculptor’s hand, guided by muscle memory and instinct. Instead, it’s a precise laser or extruder, building forms layer by minuscule layer, translating digital dreams into tangible reality. This is the world of 3D printing in sculpture, a frontier where the cold logic of technology meets the warm, expressive soul of art. What was once a niche manufacturing process has blossomed into a powerful creative medium, fundamentally altering how artists conceive, design, and fabricate their work. It is not merely a new tool; it is a new language for form, texture, and possibility.

The journey of a 3D-printed sculpture begins not with a block of stone or a lump of clay, but within the boundless realm of digital space. Artists wield software like digital clay, sculpting complex, intricate forms that would be unimaginable—or impossibly time-consuming and fragile—to create by traditional means. They can design organic, lattice-like structures that mimic natural bone or coral, create impossibly delicate interlocking parts, or engineer forms that defy gravity itself. This digital freedom is the first and perhaps most profound gift of the technology. The artist is liberated from many physical constraints, allowing pure conceptual exploration to drive the design process.

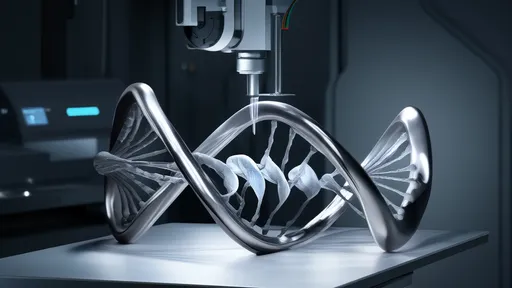

Once the digital model is complete, the manufacturing process begins, and here lies another revolution. Various 3D printing technologies offer a stunning array of material choices, each with its own aesthetic and structural properties. Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) fuses fine nylon powder into strong, durable forms, often with a slightly granular surface texture that becomes a feature of the piece. Stereolithography (SLA) uses a laser to cure liquid resin, achieving breathtaking levels of detail and smoothness perfect for intricate figuratives. For larger, more architectural works, Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) builds up robust forms with plastics like PLA or ABS, their visible layer lines sometimes left as a testament to the object's origin. And at the highest end, artists are now printing directly in metals like bronze, stainless steel, and even precious silver and gold, using binder jetting or direct metal laser sintering, creating works that are both cutting-edge and timeless.

This technological shift is not about replacing the sculptor; it’s about expanding the sculptor’s palette. The relationship between artist and machine is a collaborative dialogue. The artist must understand the material behaviors, the structural implications of overhangs, the need for supports, and the finishing techniques required for each technology. This knowledge becomes part of the creative calculus. Furthermore, the process often involves a hybrid approach. A printed form may serve as an armature for traditional hand-sculpting, a precise master for mold-making and casting, or one component in a larger assembled piece. The hand of the artist is ever-present, from the initial digital sculpt to the final finishing touch, guiding the technology to serve a creative vision.

The implications of this fusion extend far beyond the studio walls. 3D printing democratizes access to complex fabrication, allowing artists without access to industrial workshops or foundries to realize ambitious projects. It enables the precise replication and scaling of works, opening new possibilities for editions and public art. Perhaps most excitingly, it facilitates unprecedented collaboration. An artist in Tokyo can design a sculpture and have it printed locally in London or New York, shrinking the logistical barriers of the art world. Conservationists are using 3D scanning and printing to create perfect replicas of fragile ancient sculptures for study and display, while also manufacturing custom tools and parts for delicate restoration work.

Yet, with these new possibilities come new questions that the art world is only beginning to grapple with. The concept of the "original" becomes blurred in an age of perfect digital replication. If a sculpture exists as a file, and identical copies can be printed anywhere, what constitutes the authentic artwork? Is it the file itself, the first print, or a limited series of signed and numbered prints? Furthermore, the very nature of authorship is tested. Does the programmer who wrote the algorithm for a generative design share credit with the artist who parameters it? These are not simple questions, and they challenge traditional notions of value, ownership, and creativity in art.

Looking forward, the horizon of digital fabrication in art stretches with dizzying potential. Researchers are experimenting with 4D printing, where objects are printed with materials that change shape over time when exposed to stimuli like water or heat, introducing the dimension of time into sculpture. Multi-material printing allows for objects with graduated hardness, color, and transparency within a single print job. As printing scales increase, we will see more architects and artists creating large-scale environmental works and installations directly from digital files. The boundary between the designed object and the living, reacting organism is beginning to soften.

In conclusion, 3D printing is far more than a novel production method for sculpture. It represents a fundamental paradigm shift, a new way of thinking about and making art. It bridges the gap between the intangible idea and the physical object with a fidelity and flexibility never before possible. While it introduces complex questions about authenticity and process, it simultaneously offers breathtaking new tools for expression. It empowers artists to materialize the previously immaterial, to build the once-unbuildable, and to explore a new frontier of form. This is not the end of traditional sculpture; it is the vibrant, exciting beginning of a new chapter in the ancient story of humanity's desire to shape its world. The digital chisel is here, and it is carving out a bold future for art.

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025