In the ever-evolving landscape of artificial intelligence, one of the most intriguing developments has been the emergence of AI systems capable of analyzing, interpreting, and even creating art. This new frontier, often termed computational aesthetics, is not merely a technical achievement but a profound cultural shift, forcing a re-examination of age-old questions about creativity, interpretation, and the very essence of art itself. The dialogue between machine analysis and human creation is generating a vibrant, and at times contentious, discourse within the global art community.

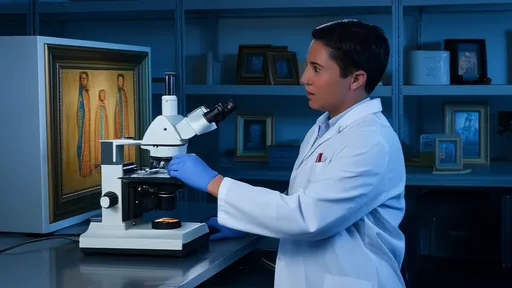

The core of this movement lies in the development of sophisticated algorithms trained on vast datasets of human art—from the cave paintings of Lascaux to the digital installations of today. These systems learn to recognize patterns, styles, compositions, and color theories that have defined artistic movements throughout history. By processing millions of images, an AI can deconstruct a Rembrandt portrait into its constituent elements: the masterful use of chiaroscuro, the emotional depth captured in the subject's eyes, the specific brushstroke techniques that create texture and life. It doesn't *feel* the emotion, but it can map its visual triggers with astonishing precision.

This analytical power leads to the first major point of discussion: can a machine truly understand art? Proponents argue that AI offers a form of ultra-objective criticism, free from the subjective biases, cultural baggage, and personal tastes of a human critic. It can identify influences and connections between artists that might escape the human eye, creating a data-driven art history. For instance, an algorithm might quantitatively demonstrate the stylistic evolution of Picasso by analyzing the geometric fragmentation across thousands of his works, providing a new, empirical narrative of his career.

However, this purported objectivity is also its greatest limitation. Detractors contend that art's primary value lies in its subjective, emotional, and often ineffable impact on the human viewer. Reducing the Mona Lisa to a set of data points about sfumato and composition misses the entire point of the experience—the mystery of her smile, the cultural weight the painting carries, the personal connection a viewer might feel standing before it in the Louvre. An AI can describe how a piece is made, but it cannot access the why—the artist's intention, their emotional state, or the socio-political context that fueled the work's creation. This creates a fundamental gap between analysis and comprehension.

Beyond mere analysis, the field has exploded with AIs that move into the realm of creation. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) and other models are now producing paintings, composing music, and writing poetry that is often indistinguishable from human-made work. This development forces an even more uncomfortable question: if the output is aesthetically pleasing or emotionally resonant, does the origin matter? The art market has already begun to grapple with this, with AI-generated pieces selling at major auction houses for significant sums. This challenges traditional definitions of authorship and creativity, suggesting that the artist's role may be evolving from sole creator to curator or collaborator who guides and refines the output of an algorithmic system.

The interaction is becoming a two-way street. Just as machines interpret human art, human artists are increasingly using AI as a tool for interpretation and inspiration. They feed classical works into algorithms to generate new, hybrid styles—a fusion of Van Gogh and vaporwave, for example—or use AI to analyze the emotional cadence of a symphony to inform the visual composition of a accompanying video piece. This symbiotic relationship is giving birth to entirely new art forms and methodologies, blurring the lines between tool and creator and expanding the palette of what is possible in artistic expression.

Ethical and philosophical questions abound in this new territory. Who owns the copyright to an artwork conceived by a human but executed by an AI trained on the copyrighted works of thousands of other artists? Can an algorithm be biased in its artistic interpretations? If its training data is overwhelmingly composed of Western art, will it fail to properly appreciate or even recognize the artistic merits of Eastern or Indigenous art forms? These are not hypotheticals; they are active debates happening in courtrooms, universities, and studios around the world, highlighting how technology forces us to constantly re-negotiate our cultural frameworks.

Ultimately, the rise of AI in art criticism and creation does not signal the end of human artistry but rather its amplification and transformation. The machine's gaze offers a mirror, reflecting back the patterns and structures of our own creativity in ways we could never see ourselves. It provides a new lens, a new set of tools, and a new provocateur in the eternal conversation about what art is and what it means to be human. The most exciting outcomes will likely not be from AI replacing the human critic or artist, but from the collaboration between the two—a partnership where human intuition and machine intelligence combine to explore the deepest questions of beauty, meaning, and expression.

As this field continues to mature, it promises to democratize art criticism to some extent, provide artists with powerful new assistants, and offer the public novel ways to engage with and understand art. The journey of machines learning to interpret human creation is, in itself, a fascinating chapter in our own creative history, revealing as much about our desire to codify and understand beauty as it does about the capabilities of the technology we build.

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025