The intersection of art and biotechnology represents one of the most provocative frontiers in contemporary creative and scientific practice. As the boundaries between organic and synthetic, living and non-living, and even ethical and aesthetic continue to blur, a new genre of artistic exploration is flourishing within the laboratories and studios of pioneering individuals. This is not merely art about science, or science illustrated through art; it is a profound synthesis where biological processes become the medium, and scientific inquiry merges with poetic expression. The dialogue between these two seemingly disparate fields is generating works that challenge our very definitions of life, authorship, and the nature of creation itself.

Historically, artists have always looked to the natural world for inspiration, but the tools of representation were traditionally limited to pigment, stone, or sound. The late 20th century saw the emergence of bio-art, a movement where artists began to collaborate directly with biologists, geneticists, and ethicists. They started employing the technologies of life sciences—such as tissue culture, genetic engineering, and molecular biology—as their palette and canvas. Pioneers like Eduardo Kac, with his infamous fluorescent green rabbit Alba, genetically modified to glow under blue light, thrust this nascent field into public consciousness, sparking worldwide debates that oscillated between awe at the technological marvel and deep ethical concern. This was no longer a static depiction of nature; it was an intervention into its very code.

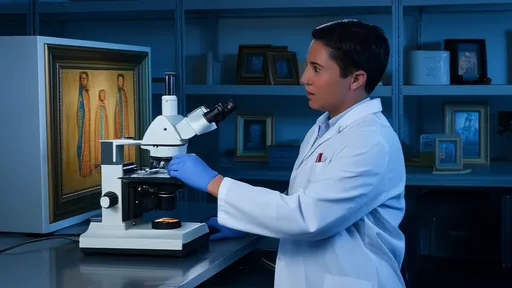

The laboratory, once a sterile space of pure data and objective analysis, has been reimagined as an artist's studio. Here, the petri dish replaces the sketchbook, and microscopes serve as lenses for a new kind of perception. Artists-in-residence at scientific institutions work with living cells, bacteria, and DNA sequences, treating them as malleable materials. For instance, the collective SymbioticA at the University of Western Australia has been instrumental in fostering this practice, enabling artists to engage in hands-on experimentation. Their projects have ranged from growing semi-living sculptures from tissue cultures to creating leather-like materials from cultured cells, forcing viewers to confront the materiality of life and the future of manufacturing.

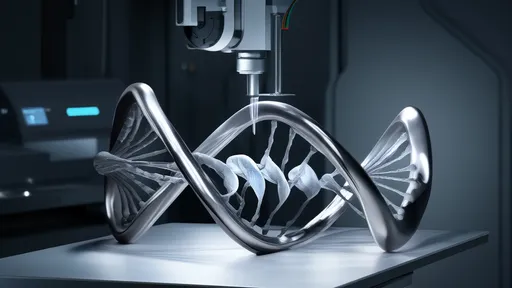

At the heart of much of this work lies a deep engagement with DNA, the fundamental code of life. Artists utilize techniques like PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) and CRISPR gene editing not for medical research, but for conceptual exploration. They might sequence their own DNA to create a personal portrait in the form of a unique genetic barcode, or edit the genes of a simple organism to produce patterns or colors, effectively programming life to express an aesthetic vision. This practice raises profound questions: If an artist engineers a new form of life, who is the author—the scientist, the artist, or the organism itself? Is the artwork the genetic code, the living entity, or the cultural discourse it generates?

Beyond genetic manipulation, other artists explore the scale and process of life through breathtaking visualizations. Using advanced imaging technologies like confocal microscopy and MRI scans, they reveal the hidden, intricate architectures within a living body—the neuronal networks of a brain resembling a galactic constellation, or the vascular system of a leaf echoing a river delta. These images, while scientifically valuable, are also deeply aesthetic, presenting a sublime beauty that is inherently biological. They dissolve the line between scientific documentation and artistic composition, suggesting that nature's underlying structures are themselves a form of art.

The ethical dimension of bio-art is unavoidable and constitutes a core part of its power. These works are rarely created to provide easy answers; instead, they function as philosophical provocations. They make tangible the abstract ethical dilemmas discussed in scientific papers and policy meetings. When an artist cultivates a tiny, living ear on their arm, as Stelarc did, or creates a steak from their own cells, as Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr have explored, the public is confronted with the visceral reality of technologies like tissue engineering. The artwork becomes a site for public engagement with science, democratizing complex debates about biotechnology's promises and perils, from ecological conservation to human enhancement.

Furthermore, this fusion is not a one-way street where art merely borrows from science. The methodologies of art are increasingly influencing scientific practice. The intuitive, speculative, and holistic thinking common in art can offer scientists alternative perspectives on problems. Design thinking, borrowed from the arts, is used to improve laboratory equipment and user interfaces for complex scientific software. More fundamentally, the aesthetic choices scientists make in visualizing data—the colors chosen for a heat map, the composition of a scientific figure—are acts of communication that share a language with visual art, determining how knowledge is perceived and understood.

Looking forward, the convergence of art and biotechnology is poised to become even more significant as technologies like synthetic biology and artificial intelligence mature. We are moving towards a future where designing life could become as accessible as digital design is today. Artists will likely be at the forefront, acting as essential critical voices and cultural interpreters for these seismic shifts. They will help society navigate the emotional, spiritual, and ethical landscapes of a world where the manipulation of life is increasingly commonplace. Their work ensures that as we gain the power to redesign biology, we do not lose sight of the profound questions about value, meaning, and our relationship to the living world.

In conclusion, the exploration of art within the life sciences is far more than a niche avant-garde movement. It is a vital, critical dialogue that enriches both fields. It challenges science to consider the cultural and ethical implications of its power and reminds art of its capacity to engage with the most pressing issues of our time. By using life itself as a medium, these artists create experiences that are immediate, visceral, and unforgettable, compelling us to look closer, think deeper, and feel more profoundly about the incredible, and often unsettling, beauty of biology and our evolving role within it.

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025